I subscribed to Oliver Burkeman’s newsletter just in time.

It wasn’t that I wasn’t previously aware of Burkeman—I loved his Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, which I’ve written about in this column before—but in the way of the internet, I didn’t know he had a newsletter. (Who can keep track?) Upon discovering it, I signed up, and the first thing to land in my inbox contained this extremely-pertinent-to-my-life string of words:

“I think you should treat your ‘to-read’ pile not as something you have to get through, but as something you get to pick from.”

Did the same bells just ring in your brain?

I’m sure there are plenty of people who already have this mindset, and who look askance at those of us who are out here bemoaning the state of our TBRs, be they piles or shelves or entire bookcases or, heck, entire rooms. (I’m not that bad. Yet.) How can you complain about such bounty? I imagine them saying. What’s wrong with you?

What’s wrong with me is a long list, much of which I shan’t get into here. But this problem is hardly mine alone. You can’t venture into a bookish online space without encountering the problem of the TBR—which I have had to accept is, at least for me, a little bit of the problem of mortality, in general. I’m an anxious person. I’m anxious about time. I’m trying not to be.

But still, I exist on the internet, which is a slurry of enthusiasm, opinions, and curiosities that is hard to ignore, even if you want to. Every single day I hear about another book I want to read: My currently open tabs include pages for Manjula Martin’s The Last Fire Season: A Personal and Pyronatural History and Immediacy, or the Style of Too Late Capitalism by Anna Kornbluh, neither of which are out until January. (Will I keep those tabs open for seven months? Uh, I hope not.) My reading spreadsheet has a whole tab for books I want to read someday, some of which have been on there so long that I no longer remember why I added them in the first place. (Keeping notes about why you add a book to such a list is something I highly recommend.)

I don’t believe reading is or should be a competition, but at the same time, I look at my TBR and despair: Why haven’t I read How Long ’til Black Future Month yet? Why is Plain Bad Heroines still just sitting there? What about that book I bought in Australia in 2014, or the copy of Iain M. Banks’ The State of the Art that I ordered from the UK because I couldn’t find one here? Do you want to know how many books on this shelf were purchased when I worked at a bookstore, which I haven’t done since 2015? I sure don’t. But I remember every time I look at them.

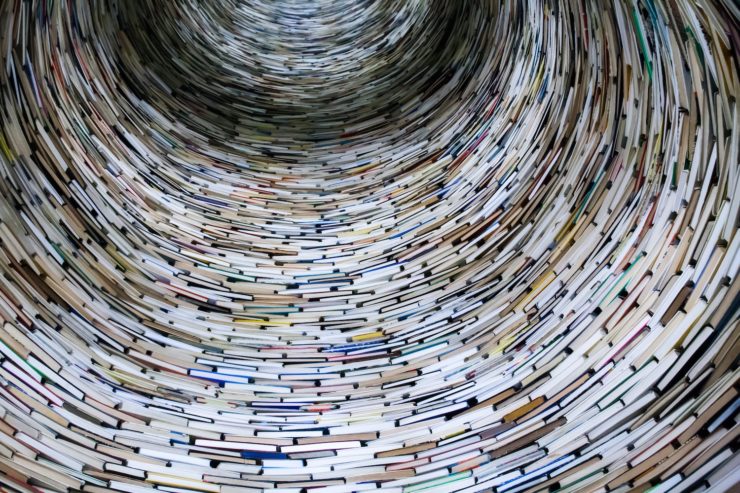

What Burkeman means, if he will forgive me for the paraphrase, is that this is not a helpful way to look at it. It is not a to-do list. It is not a mountain with a summit that can be reached by human minds or bodies. The giant TBR pile is not a bug; it is a feature. (If you have moved semi-recently, as I have, you may have a harder time with this concept. I understand.) He calls it a problem of “Too Many Needles,” a phrase he borrows from Nicholas Carr, who wrote:

When we complain about information overload, what we’re usually complaining about is ambient overload. This is an altogether different beast. Ambient overload doesn’t involve needles in haystacks. It involves haystack-sized piles of needles.

A haystack-sized pile of needles. A bookcase-sized pile of options. A thing that can’t be optimized or productivity-hacked because (a) there’s truly never enough time and (b) it’s not a to-do list or a series of tasks and (c) we’re talking about experiencing art, not some kind of bookish hustle culture, god forbid, please forgive me for even putting those words in that order.

Burkeman’s answer is to treat your TBR mountain “like a river (a stream that flows past you, and from which you pluck a few choice items, here and there) instead of a bucket (which demands that you empty it).” Being a former hippie child from the Pacific Northwest, I especially like the imagery here: A bucket is something you use to catch leaks or bail out a boat, neither of which is a particularly enjoyable experience. A river is something you gaze at, float on, appreciate; it’s something natural and wild, not plastic and tamed.

And at the best of times—when I’m not overwhelmed by the bigger problems of the world, worrying about the smoke my friends are breathing or the viruses people are still transmitting or the rising sea levels or student loans or just the general destructive trend of the world of late, full stop—when I look at the books I have yet to read, I do see a river, one absolutely full of stories that are going to be their own magic, their own journey, when I get to them. I don’t have to read the next shiny bright popular thing immediately. Neither do you. I don’t have to keep up on series or predict the future or know everything about an author before I dive into their full backlist. I have to do what I always do: try to read widely, diversely, fervently; try to read the things that will fill the well from which I write. Or rather, to keep water in that well, which also can never be full, and never be finished.

The title of this piece is purposely optimistic. I have not yet learned to stop worrying. I am learning, though. Slowly, belatedly, but better late than never. All these books I have piled up before me are a bounty, not a task. All the books in the library, all the books I could read, will read, might read: the same.

The river doesn’t even notice how I look at it. It just keeps flowing. Or sitting and gathering dust, if we set aside the metaphor. But that’s okay, too. Touching the books is, after all, part of the process.

Well said. There is a meme that I keep seeing saying that a personal library is like a wine cellar. You don’t keep it to read everything, but to have something when you are in the mood for it.

I have always treated by TBR pile like what you describe. Now it overflows my tall book shelf and I never have qualms about adding to it. Sometimes I remove things from it unread because the person I was when I bought it doesn’t have the same reading desires as I do now.

Then there are the “queue-jumpers”, the books that arrive that must be consumed as soon as possible. Usually from a handful of particular authors (that list changes over time too).

I love the fact that I will have a book on hand for any mood I am in. Though sometimes it takes me 10 years to find myself in that particular mood, then wonder why I took so long to finally read that book!

Emotional support pile you mean surely?https://twitter.com/Secondlina/status/1668309274106249216?t=U5ajniNo4XWPUZEbT9XeYA&s=19

1. Jeff S

I love that!

That is my feeling exactly. Well, that and the realization that my TBRs both physical and ebooks, are so large I’ll still be reading them two years after I’m dead

I used to have a lot of anxiety about my ever-growing backlog, then I realized that it’s like a big store from which I can buy things for free.

I still get anxiety that I’m reading new books from the library instead of books that I own. But I think making progress helps. As long as I’m not “stuck” with nothing moving out of the backlog for too long I’m okay.

But when you have a mountain of books, keep buying more, AND you’re not getting any read, that’s an unpleasant feeling.

This resonates so hard today! My one and only resolution this year was to read the books I’ve been buying, instead of checking out library books (occupational hazard). So far, I’ve kept to that, and have discovered (rediscovered?) several treasures!

Wonderful post about the merits of having books to choose from. I have an entire shelf of unread books for leisure reading and another for work (mostly environment/climate-themed, both nonfiction/academic writing and cli-fi) and have been watching the piles grow with some trepidation and stress, while my self-imposed moratoriums on buying more books have been… well. Unsuccessful is an understatement.

I call this my SBR, the Strategic Book Reserve.

I don’t look at my TBR pile as a problem. I call it “stockpiling for retirement when I can’t afford to buy books anymore”.

I started looking at my print TBR shelves (of which there are many cases full) as my curated library to read from. The silly thing? I often read actual library books (because they expire) that I’m moderately less interested in first before I look at my extensive ebook or print collection. This year I resolved to at least read the first 3 books in two series from the print shelf. Sarah J. Maas ACOTAR and Mark Lawrence’s Prince of Thorns trilogy. I then added on half a dozen other books that are either independent, local authors, indigenous or queer authors to ensure I absolutely read a variety of authors.

And yet we are halfway through the year and I’ve managed to read 1 of 6 of those books selected. Not a good track record. Lol.

I completely agree with you that I’m not sad at all to have so much great literature; but I seriously lament mortality. I’d take immortality (even as a vampire or something) in a heartbeat if it meant I could keep reading

And then I go to the Friends of the Library sale the day that all fiction is only a quarter…good thing I’ve been doing those weights now, isn’t it?

I absolutely love the Strategic Book Reserve definition! Now that I am retired I am finally delving into my Reserve, both print and electronic, but I also…..some how….keep adding to the piles….At this point I sincerely hope I inherited the long life genes from my mother’s side of the family, because otherwise I will never get through them all!

What Carr refers to as ambient overload I have always thought of as decision fatigue. So many great books to choose from that deciding itself is an exhausting process. I’ve solved the problem by numbering all my books in a journal and using a random number generator to decide my next read. After all, every single book in my huge TBR pile is a book I bought intentionally because I like the sound of it. I’m not hard and fast. If the generator throws up a book I’m not in the mood for I just generate another number. Nine times out of ten I’m happy with the first choice though.